Another chapter in the serialized 1981 travel adventure which Walhydra first published on The Crone Thread in 1997.Part 4: In Which Walhydra stands corrected, but doesn't notice for the longest time

If she's backed into a corner, Walhydra will begrudgingly admit that she's a fake. Well... maybe that's too strong a word for it, but "dilettante" sounds too pretentious.

It's important to her to be seen as one who knows the right answers, so of course that leaves lots of gaps to cover over. Despite this, fortunately, Walhydra's Virgo core won't let her lie…um…knowingly, which means that, when she's caught out, she will admit to certain things.

Like this, for example: she doesn't remember any past lives.

Knowledge will leak forward from them when she absolutely needs it—sometimes taking her by surprise—but she can't call it up at will.

Or like this: she doesn't have any sightedness or any training in secret wisdom.

She talks fast. She reads a lot. And when someone close by has a need, she finds useful things coming out of her mouth which she doesn't know she knows until she speaks them.

It's rather annoying. And humbling.

It's also why she had to give up smoking Sacred Weed. She was too readily entertained by ensorcellment and too careless of consequences. She confused imagination with revelation too easily. And she tended to get too fascinated by her own prophesying, forgetting that silence, not noise, is the fount of truth.

Given all this, when Walhydra opened her eyes upon the semicircle of New Delhi natives sitting round her half-lotus form at Connaught Place, she kept her mouth shut.

"Now I'm in for it," she thought. " 'S what I get for putting on this big saffron diaper. What an idiot!"

Amazingly, none of her polite attendants let on that she was an idiot.

They asked her intricate questions about her travels. They enjoyed her delight at the things she had seen and experienced in their country. And they did not insist that she impart any wisdom. It was a generous reprieve.

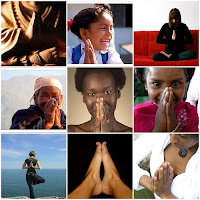

When the gathering dispersed, Walhydra stood to make her own escape, only to be faced with a small, balding, brown man in a white Nehru jacket, who made Namaste with his steepled palms and then introduced himself. D.B. Gupta, barrister.

When the gathering dispersed, Walhydra stood to make her own escape, only to be faced with a small, balding, brown man in a white Nehru jacket, who made Namaste with his steepled palms and then introduced himself. D.B. Gupta, barrister.Long ago, Walhydra's childhood mind had confused the word "barrister" with "banister."

The confusion was heightened by old illustrations of the intricate wooden podiums, balusters and jury boxes of traditional British courtrooms.

The confusion was heightened by old illustrations of the intricate wooden podiums, balusters and jury boxes of traditional British courtrooms.Thus confounded by memory, Walhydra was momentarily distracted by images of darkly varnished railings and furniture and almost missed what Gupta-gee was saying.

He was inviting her to dinner the next evening in his office-cum-flat in another part of the city. Before she could find an excuse, Walhydra had accepted the offer.

Gupta-gee gave her elaborate directions for autobus connections and street turnings, accepted her assurance that she too was vegetarian, and bowed farewell with another Namaste.

"What in the world have I started now," Walhydra wondered. "Is this saffron some kind of invitation to trouble?"

Spouse Nikki just giggled when she told him the story. "You asked for the job, Sunshine."

"But Nik-keee-eee...."

"You're an adult. You'll cope."

As usual, the Aquarian hubby's way of helping out was to toss Walhydra into the deep end.

Blub, blub, blub....

The next evening, crowds of polite Indians watched as a thirtyish American faggot, wrapped in orange swaddling clothes and necklaces and wandering half way round the world from home, hopped from street to autobus to street in the least European part of Old Delhi.

To complete the picture, the gentle reader needs to know that, in India, any available surface of a bus can carry passengers.

To complete the picture, the gentle reader needs to know that, in India, any available surface of a bus can carry passengers.Walhydra had chosen not to hang from the outside window frames, as did a dozen or so others. She managed, instead, to squeeze into the side stairwell—hoping the saffron dhoti wouldn't come loose and leave her naked in the press.

At her stop—she hoped it was her stop—she climbed down, clothing fortunately still intact. The late afternoon sun showed her dusty, unpaved streets, ageless brick and stucco walls...and no street signs.

Still, following her directions, she was able to make her way to one high and nondescript wall, in the middle of which stood a wood-framed doorway and D.B. Gupta, the latter greeting her once more with the sacred gesture of peace.

Gupta-gee ushered Walhydra into a tiny space, two cubicle-sized rooms joined by an open archway. The farther room had the clerkly look of all those civil servant spaces in which she had spent so many unpleasant hours of late. The room in which Gupta-gee offered her a seat was what the British would call a "bed-sitter."

There was a couch or divan, upon which host and guest sat and which—the clever reader will have surmised—doubled as a bed. There were copiously filled bookshelves. Somewhere behind a curtain there was a source of water, storage space and, perhaps—Walhydra never dared ask—a water closet or some such contrivance for discrete biological processes.

And, to complete the bed-sitter format, there was a "cooker" in the middle of the floor. This one was not, however, the ubiquitous electric hotplate of British habit. It was a cylindrical charcoal-burning contraption upon which sat a vat of boiling water and a vegetable steamer.

Gupta-gee explained, as he pared and sliced a marvelous variety of vegetables into the steamer, that his strict but adequate daily diet consisted of these vegetables and two liters of warm, fresh whole milk. He needed no food storage space, since he bought these items in the local market just before each meal.

Walhydra watched as onions, various squash-like items, lotus pods and other nameless things dropped into the mix. Though it was served entirely unseasoned, Walhydra was surprised at the variety and distinctness of flavors in the finished product.

As if sensing her surprise, Gupta-gee smiled slightly and said, "The simpler the better."

Through their evening conversation, Walhydra learned that her host had a wife and three children, whom he supported yet with whom he did not live. He had some years earlier adopted a strict yoga discipline which included, in addition to his diet and exercise regimen, both celibacy and his present solitary life.

Anticipating his Western guest's skepticism, Gupta-gee assured Walhydra that his wife and family were fully in support of this ascetic separation. It was a time-honored path for parents of nearly-grown children in certain Hindu families.

Walhydra nodded, vaguely humbled.

The rest of the evening was rich and pleasant, yet, to her dismay as she retells the story now, Walhydra realizes that she remembers almost nothing of the conversation.

In those youthful years, Walhydra's attention was still distorted by a non-clinical, adolescent form of what is sometimes called ideas of reference. In other words, "Everything that happens is happening to me."

When she had made her way back to Husband #3 later that evening, Walhydra was delighted to tell him of her adventure. The bus rides and the passengers hanging from the windows, the bed-sitter, the strange meal, the host's asceticism. Yet the story was still all about her adventure.

Only now, years later, does she notice something simple.

Gupta-gee wore no saffron. Nor had any of the folk who sat round her at Connaught Place.

Walhydra had, to be fair, not really pretended to any holiness throughout this escapade. Yet the people in the park, and Gupta-gee in his tiny flat, had all treated her with politeness and—yes—reverence.

As she ponders the whole story now, she wonders:

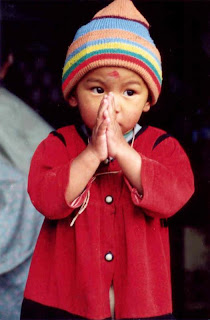

"Perhaps putting on the saffron was not an act of declaring oneself a holy man. Perhaps it was an act of asking to be shown what being a holy man might be."

[Continued in WWSA, Part 5]

No comments:

Post a Comment